About Me

Hi, I'm Megan Weiner Mansfield! I'm an Assistant Professor at University of Maryland's Department of Astronomy.My research broadly focuses on the spectroscopic characterization of exoplanet atmospheres. I use a variety of ground-based and space-based telescopes to detect molecules in exoplanet atmospheres, and I use these detections to study planetary formation, physics, and chemistry, including studying the habitability of small, Earth-sized exoplanets.

I got my Bachelor's degree from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2016, with a dual major in Physics and Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences. I received a Ph.D. in Geophysical Sciences from the University of Chicago in 2021. My thesis work focused on both observations and modeling of highly irradiated exoplanets, ranging in size from Earth-sized terrestrial planets to gas giants larger than Jupiter. I was a NASA Sagan Fellow at University of Arizona's Steward Observatory from 2021-2024 and a 51 Pegasi b Fellow at Arizona State University's School of Earth and Space Exploration from 2024-2025.

Outside of work, I like to run, cook (especially foods with chocolate and peanut butter), play board games with my husband, and dote on my cats, Orion and Luna. I also sing and play viola, and occasionally spend too much time thinking about Taylor Swift's latest music.

Research

My group's research broadly focuses on the spectroscopic characterization of transiting exoplanet atmospheres. We use a variety of ground-based and space-based observations to study planetary formation, physics, chemistry, and habitability. Here are a few of the specific projects we've worked on recently:

Recent/Ongoing Projects

Lava Lamps: Searching for Silicate Vapor Atmospheres

Lava Lamps program logo, courtesy of Lindsey Wiser

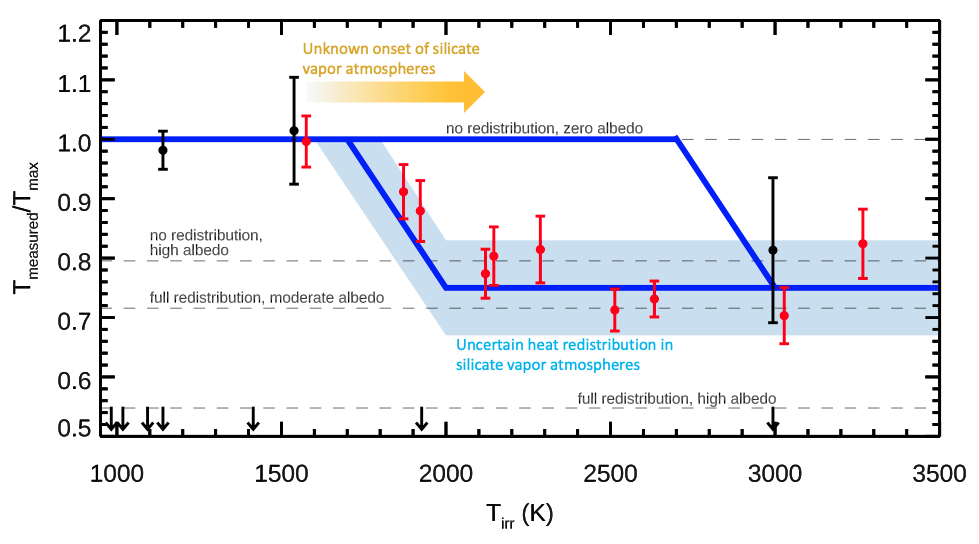

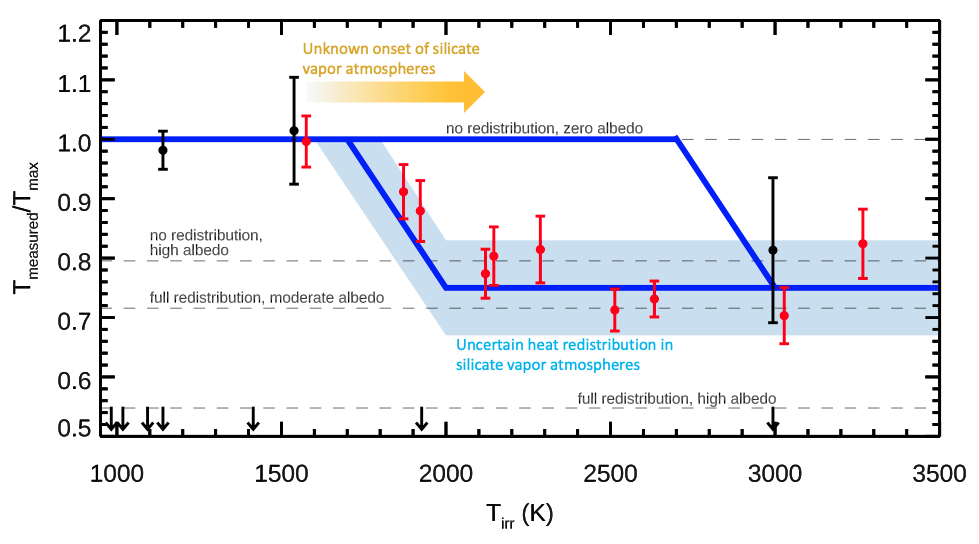

The hottest known terrestrial planets ("ultra-hot rocky planets", with irradiation temperatures 2000 K or higher) may be hot enough that their solid rock surfaces begin to evaporate, producing vaporized rock atmospheres over lava surfaces. However, there are many things we don't understand about how these atmospheres form and evolve.

The Lava Lamps survey is a JWST program to search for atmospheres on ten planets spanning in temperature from 2000 K - 3000 K. The main goal is to identify the turn-on temperature for silicate vapor atmospheres, as well as begin to investigate qualities such as how well these atmospheres transport heat to the much colder nightsides of these ultra-hot planets. Stay tuned for results!

The lava lamps sample (red points, showing simulated precisions on measured temperatures) compared to existing observations (black points).

Searching for Volatile Atmospheres on M-Earths

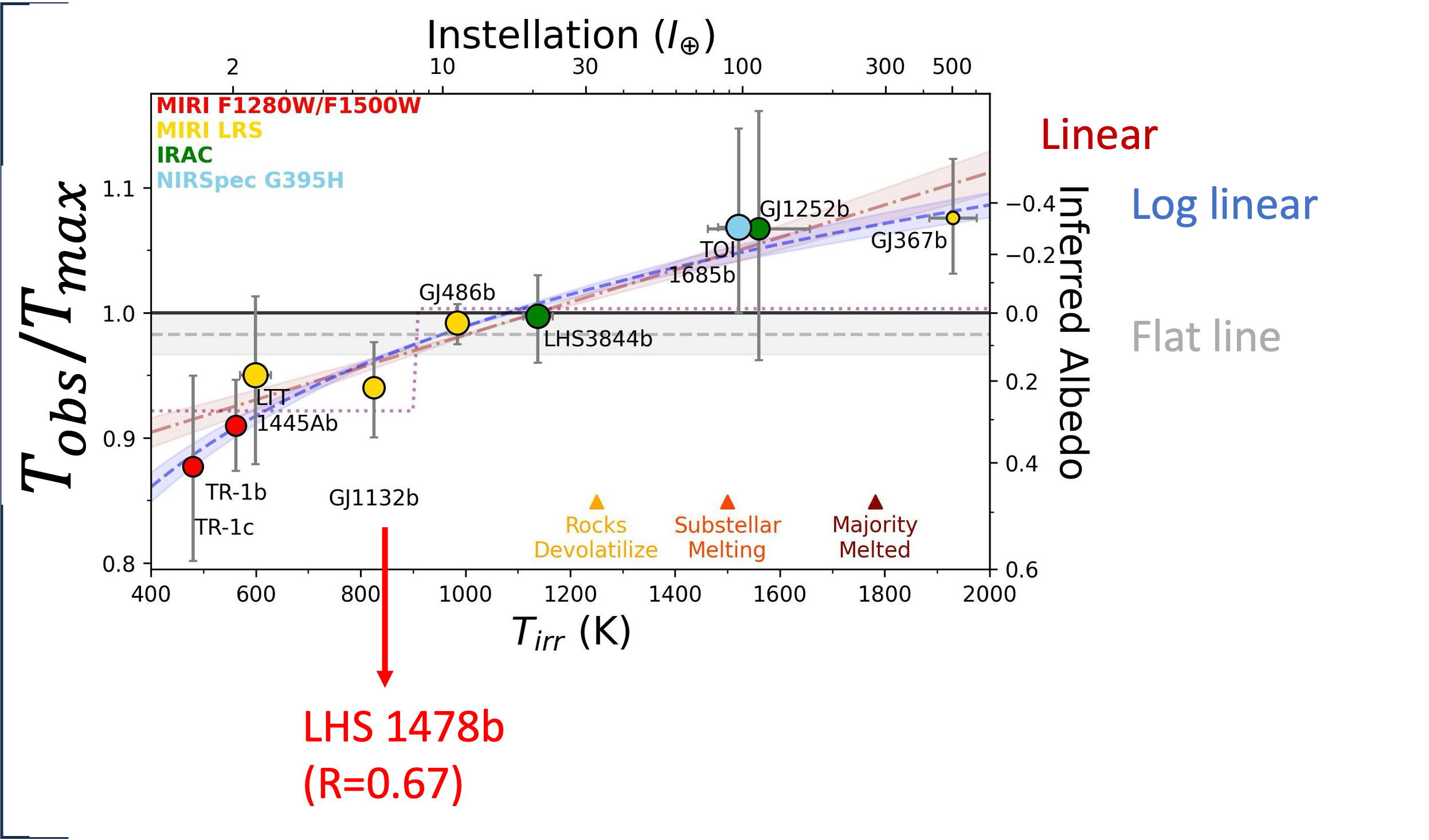

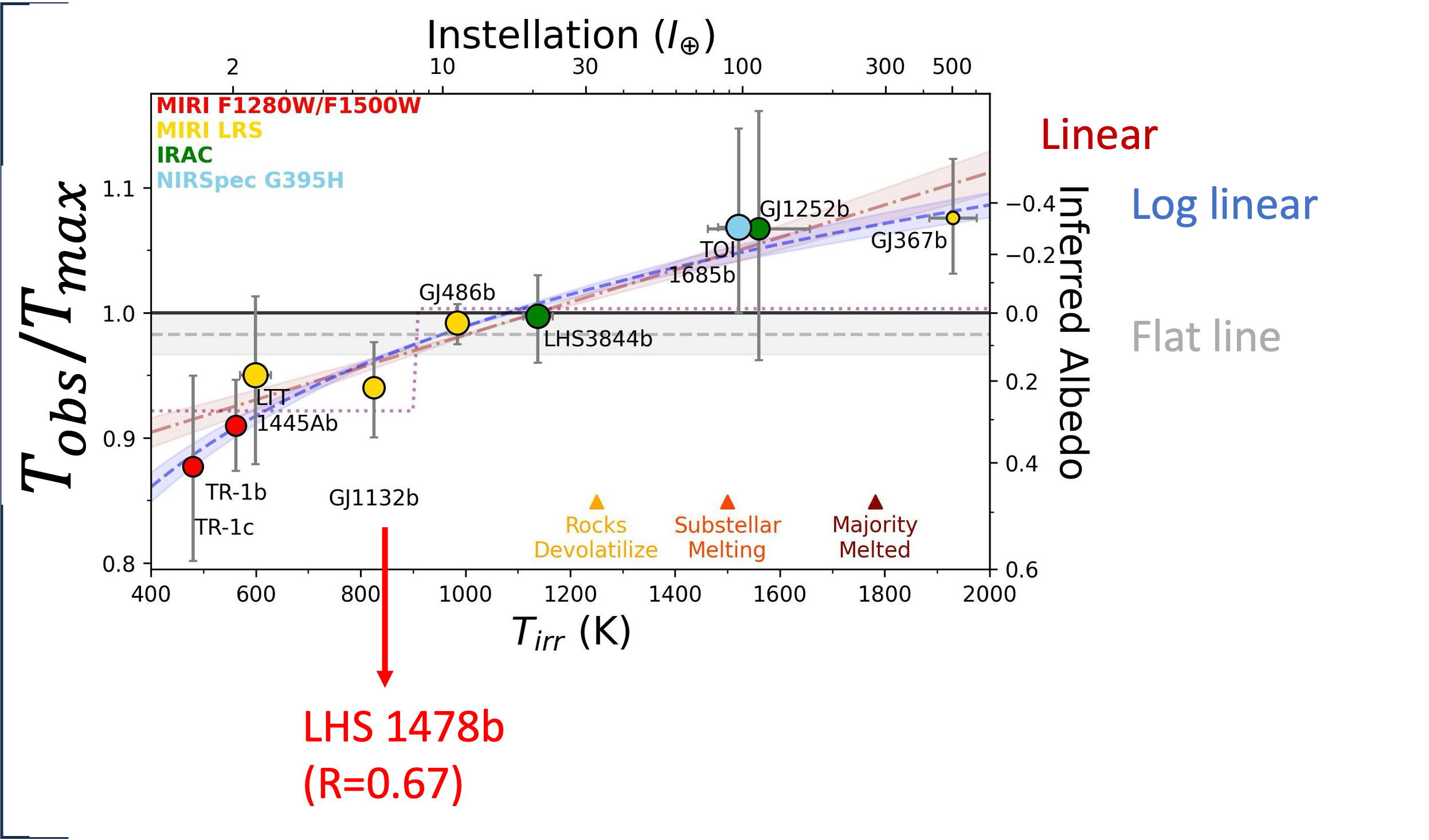

JWST will give us the first chance to observe the atmospheres of habitable exoplanets in detail, and even search for biosignatures. In order to make the best use of this resource possible, my collaborators and I conducted a study to identify the most efficient method for finding terrestrial planet atmospheres (see the papers here). We found that secondary eclipse photometry using JWST's MIRI instrument could identify atmospheres in as little as a single observation. The basic idea behind this method is that a planet without an atmosphere will have a dark, hot surface. An atmosphere will act to decrease the observed dayside temperature by either hosting high-albedo clouds and/or transporting heat to the nightside.

We recently applied this method to a handful of hot terrestrial planets and have begun to search for trends among the ~10 planets already observed with this technique. The data tentatively favor a trend toward cooler daysides at lower amounts of stellar irradiation, which could potentially be a sign of atmospheres at lower irradiation. However, the trend could also be explained by surface effects such as space weathering or grain size differences. Read more about this trend, and the individual planet results from our collaboration, here!

A tentative trend in dayside temperature with stellar irradiation, from Coy & Ih et al. (2024). A value farther below 1 on the y-axis indicates a dayside cooler than expected for a zero-albedo bare rock surface (a potential indicator of an atmosphere).

In the next few years, the Rocky Worlds DDT program will use 500 hours of JWST time to search for atmospheres on terrestrial exoplanets using the secondary eclipse photometry method. The program is just beginning, so keep an eye on the Rocky Worlds website for updates!

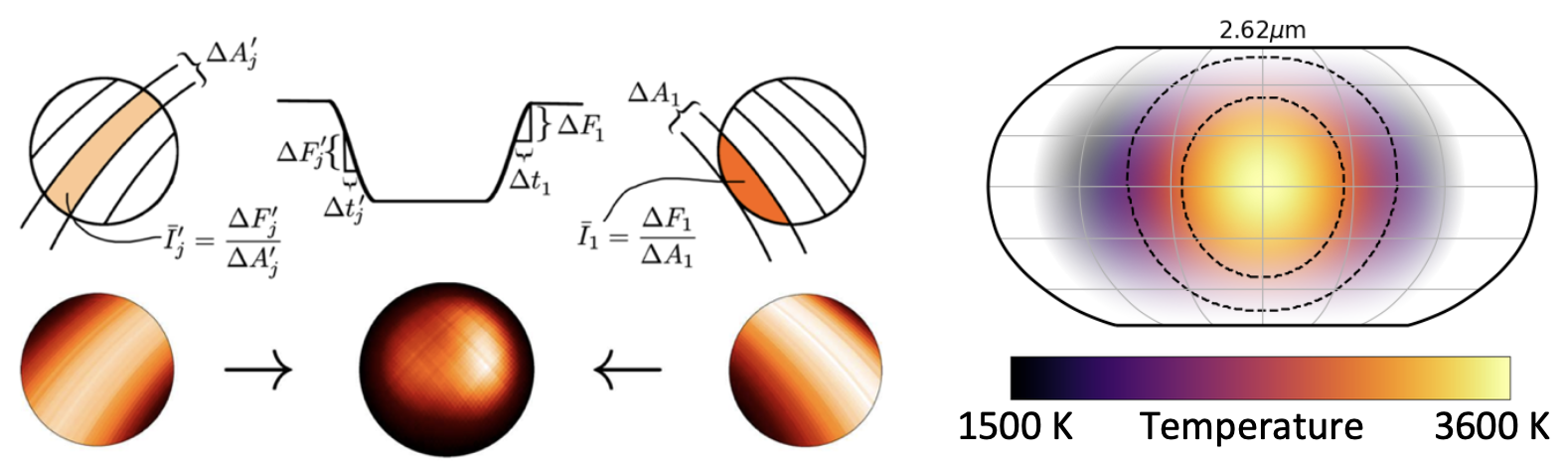

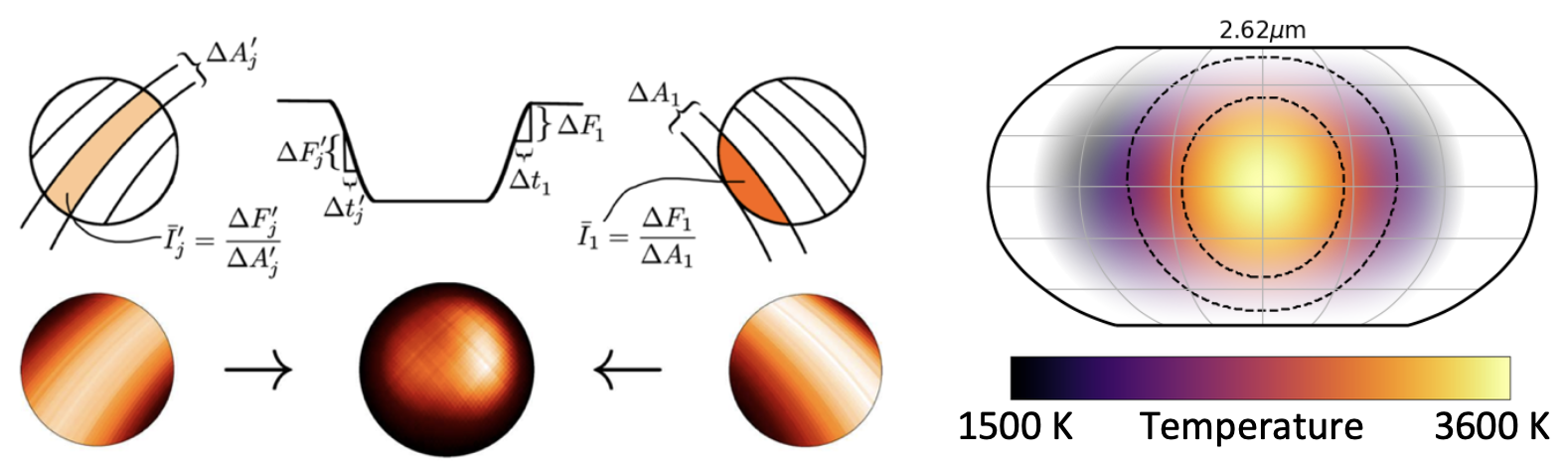

Eclipse Mapping

Most techniques for observing exoplanets produce a measurement that is averaged over a significant portion of the atmosphere, because these planets are too far away to be spatially resolved. However, the technique of spectroscopic eclipse mapping can resolve exoplanet atmospheres in three dimensions - latitude, longitude, and altitude. This is done by observing the planet during the ingress and egress of the eclipse, when it segment by segment disappears behind the star and segment by segment reappears. By combining these data, you can create a 2D grid in latitude and longitude across the dayside. Observing at different wavelengths extends this grid to a third dimension, as different wavelengths will probe different altitudes in the atmosphere.

I led the development of the Eigenspectra technique to interpret spectroscopic eclipse mapping data from JWST. I recently applied this technique to a JWST eclipse of WASP-18b to get the first resolved 3D measurement of the dayside of a hot Jupiter (paper link coming soon).

The Eigenspectra eclipse mapping code is publicly available on GitHub for anyone who wants to try their hand at eclipse mapping. University of Maryland grad student Brian Davenport is developing this method further and applying it to more JWST data sets, so keep an eye out for new updates!

Left: the geometry of eclipse mapping, from Majeau et al. (2012). Right: a single-wavelength eclipse map of WASP-18b, from Challener & Weiner Mansfield et al. (submitted).

High-Resolution Transits

A new technique that is being used to study exoplanets is ground-based, high-resolution observations. These observations rely on the fact that the exoplanets we're looking at are moving quickly around their host stars. This motion induces a Doppler shift in their absorption lines, so when you're observing a planet from the ground you can use that shift to separate out lines originating from the planet and those which belong to the star or the Earth's own atmosphere. Once you have the planet's lines separated out, you can use cross-correlation to detect signatures of individual gases such as carbon monoxide and water, and compare your observations to models to measure their abundances.

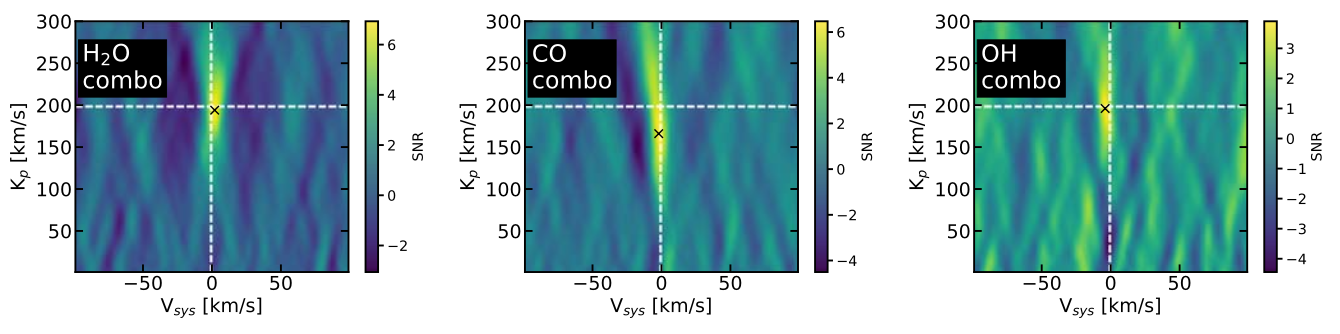

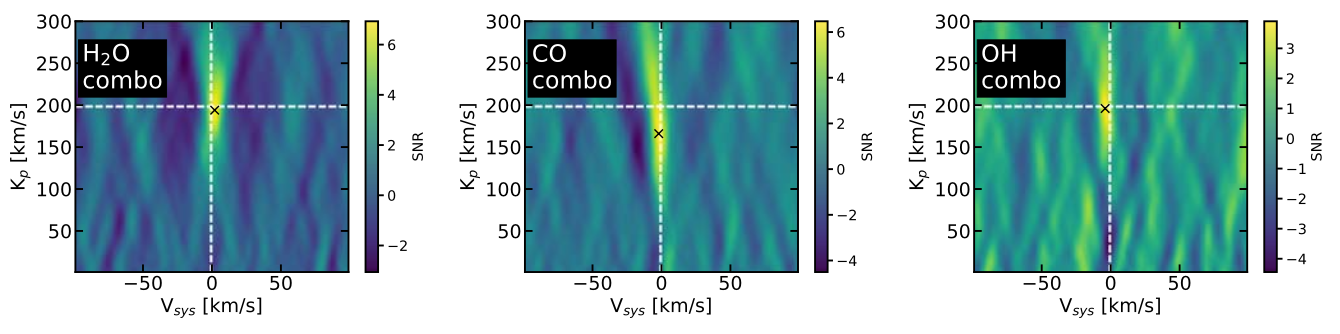

Figure from Weiner Mansfield et al. (2024), AJ, 168, 14.

I led a high-resolution survey of 10 transiting exoplanets using the Gemini-S/IGRINS spectrograph, which was located on Cerro Pachon in Chile. The goal of this survey was to precisely measure the abundances of key gases such as water in these exoplanets' atmospheres and to look for trends in abundances with parameters such as planet mass. Three results from this survey have been published: detections of water, CO, and OH in the ultra-hot Jupiter WASP-76b, a precise water abundance constraint for the hot Jupiter WASP-43b (led by University of Arizona undergraduate Dare Bartelt), and a super-solar metallicity from water and CO detections for WASP-127b (led by Arizona State University grad student Krishna Kanumalla).

JWST Early Release Science

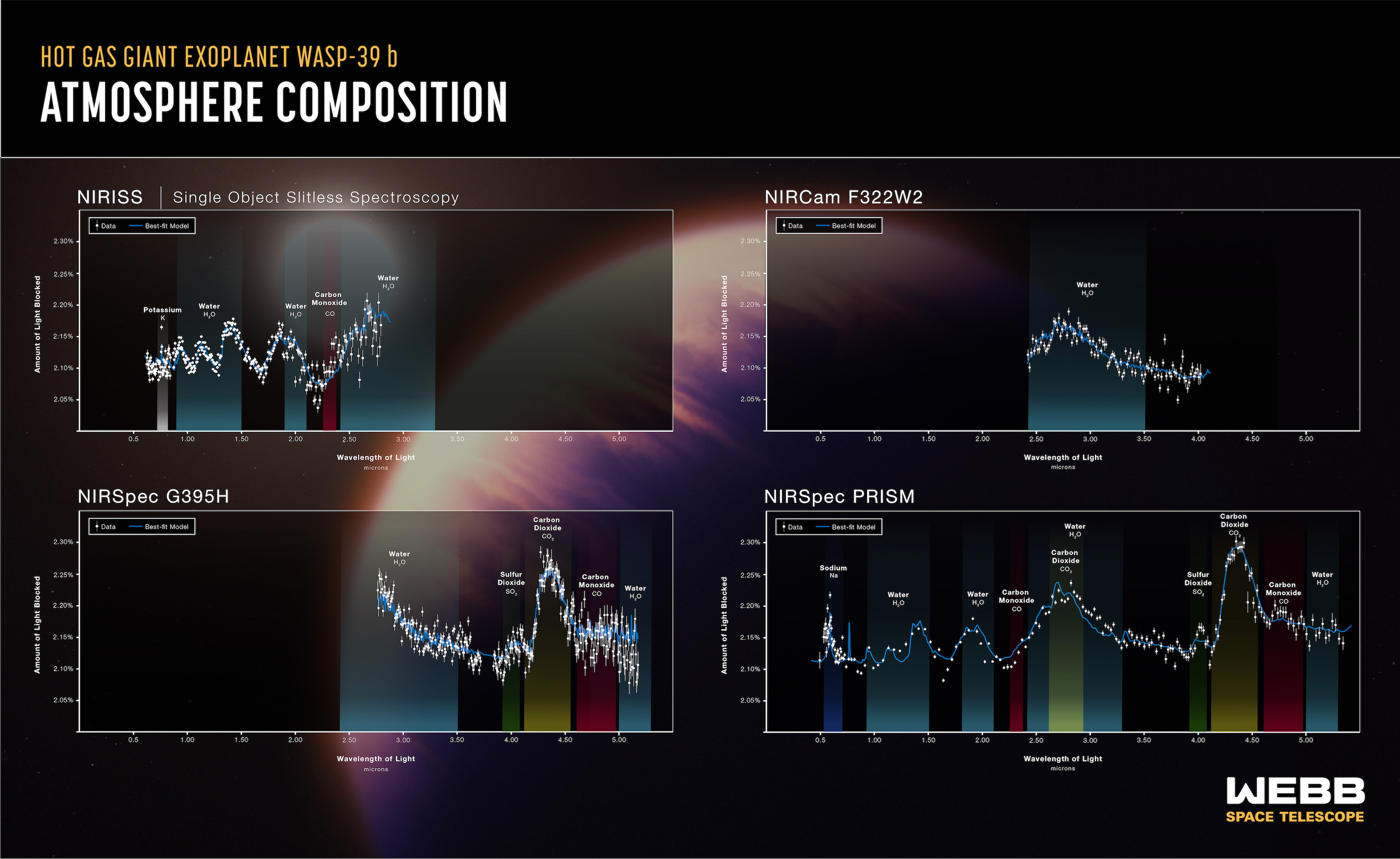

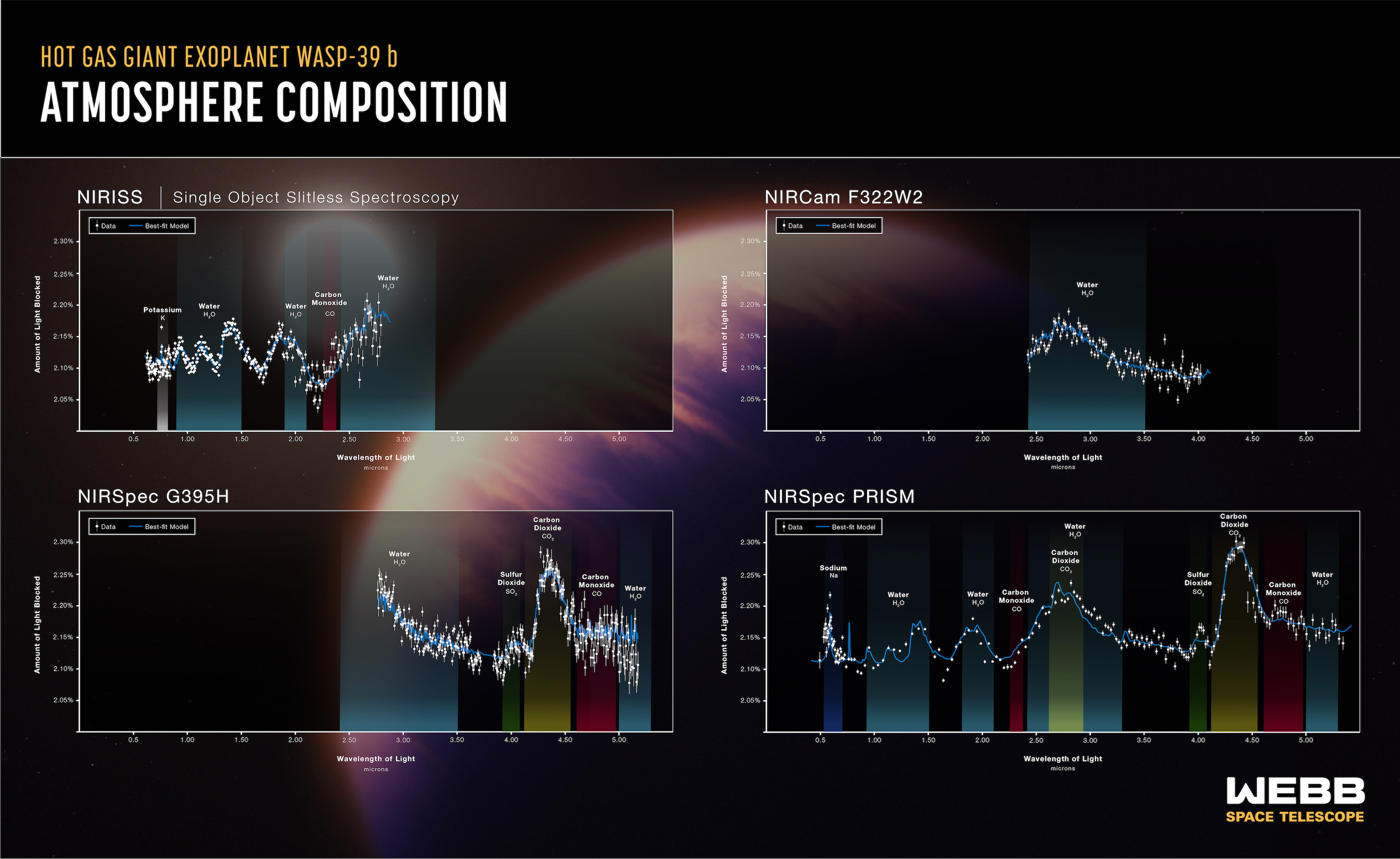

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which launched in December 2021 and began taking data in July 2022, is already revolutionizing our understanding of exoplanet atmospheres. As part of the Transiting Exoplanet Early Release Science Team, I contributed to an in-depth study of the hot Jupiter WASP-39b with JWST. This study was designed to precisely characterize the atmosphere of WASP-39b while also testing out different instrument modes to provide guidance to the exoplanet community about which observing methods work best for exoplanet observations with JWST.

The first results from this program were recently published in a set of six papers. We detected new molecules never before resolved in exoplanet atmospheres, such as carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide. In addition, the detection of sulfur dioxide indicates the presence of active photochemistry (chemical reactions driven by interaction with the star's light) in the atmosphere of WASP-39b, because without photochemistry that molecule would not be expected to be detected. This is perhaps the most in-depth study of an exoplanet atmosphere ever conducted and demonstrates the incredible potential of JWST to revolutionize the field of exoplanet atmosphere characterization!

Interested in learning more about this amazing result and some of the folks who made it possible? Check out the NASA press release here, a University of Arizona press release summarizing the contributions of some Arizona folks here, and a YouTube video by Ryan MacDonald summarizing the science here!

Figure credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, J. Olmstead (STScI).

Older Projects

Hot Jupiter Thermal Structures

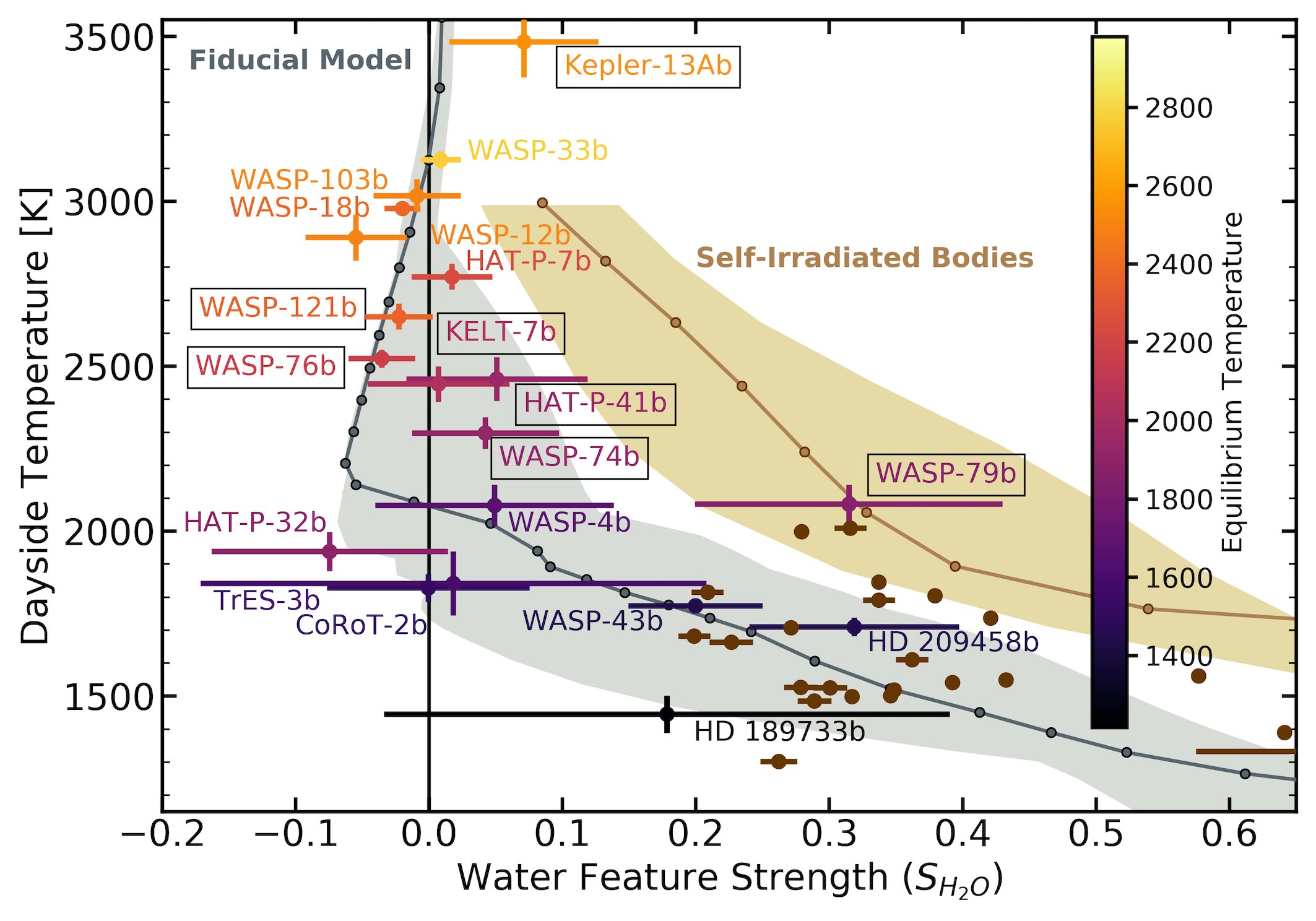

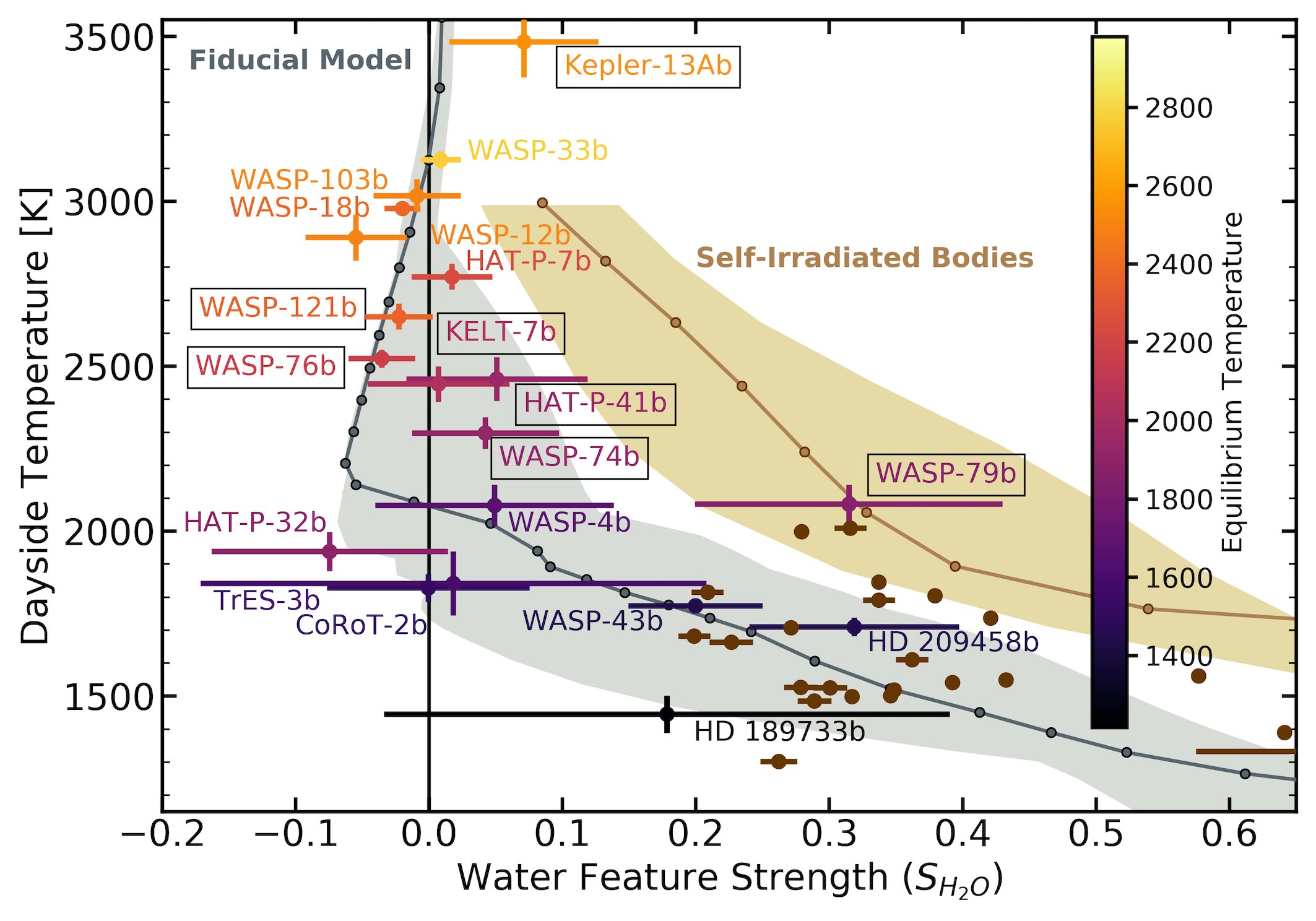

Much of my research has focused on understanding the thermal structures of hot Jupiters, which are hot gas giants orbiting close to their host stars. (Seriously, these planets get really hot!) Recently I conducted a population study of all of the hot Jupiters which have been observed in secondary eclipse with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). I created a metric to quantify the strength of the water features observed in absorption or emission in these planets' HST spectra. The observed planet population (shown in the figure below) roughly agrees with predictions from self-consistent 1D models. However, the data show substantial scatter in their water feature strengths, which we think may be due to compositional differences in their atmospheres. See the paper here for more details!

Figure from Mansfield et al. (2021), Nature Astronomy, 5, 1224.